ISBN 1-890689-02-5; $39.95

ISBN 1-890689-11-4; $29.95

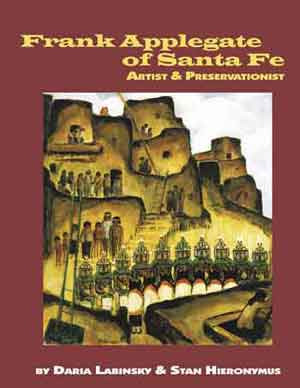

2001, 304 pp; 106 color and 61 b/w illustrations

2002 SOUTHWEST BOOK AWARD, BORDER REGIONAL LIBRARY ASSOCIATION

This is the first significant book on Applegate's life and is written by Daria Labinsky and Stan Hieronymus who live in Rio Rancho, New Mexico. Hieronymus is the great-nephew of Applegate and was able to use family papers as well as photos taken by Ansel Adams. Applegate was already an artist of some fame when he moved to Santa Fe in 1921. Applegate, along with Mary Austin, founded the Spanish Colonial Arts Society. Applegate made santos, watercolors, oils, ceramics, and woodblock prints. His art is part of the permanent collections of Regis University in Denver, The Museum of Fine Arts in Santa Fe, The Spanish Colonial Arts Society, and many others. According to LPD Press Senior Partner, Paul Rhetts, "It is appropriate on the 75th anniversary of the founding of the Spanish Colonial Arts Society to release this definitive biography of one of the important arts leaders of New Mexico. There may be many more pieces of Applegate's work out there that come to light when scholars and collectors have a chance to see this book."

Authors

Daria Labinsky and Stan Hieronymus are former newspaper editors with more than 30 years of journalism experience between them. They have written three books and hundreds of newspaper, magazine, and online articles on subjects including travel, art, music, and brewing. Stan was fortunate enough to have been born into the Applegate family - his father, Thomas Applegate Hieronymus, is Frank Applegate's nephew. Soon after their marriage in 1988, the couple began researching Frank Applegate's life and work. They live in Rio Rancho, New Mexico.

What People Are Saying

While I never had the good fortune of knowing Frank Applegate personally (he was one of the first Santa Fe Art Colony artists to pass away, dying in 1931), my career and family life have been greatly enriched by his legacy. Representing Applegate's estate and living in his former home for more than two decades has brought me closer to this overlooked artist's passion and spirit. Applegate was somewhat of a paradox because he was both a staunch defender of traditional Hispanic and Native American arts and a maverick who painted in a modernist style, keeping his hand on the pulse of the burgeoning art scene in Santa Fe during the Roaring Twenties. Applegate's love of Santa Fe's tricultural character is preserved in the place that was closest to him: the historic de la Peña House. This dwelling, which he began renovating in 1926 without compromising its eighteenth century Spanish Colonial core, was his Santa Fe home. It has also been the place my family and I have called home for more than twenty years, and it is through this shared framework that I have gleaned passing impressions of Applegate's passions and historical importance. Existing photographs of this property taken by his friend, photographer Ansel Adams, and others show that Applegate decorated his adobe home sparsely with Spanish Colonial decorative arts and furniture as well as Native American pots and textiles. My wife, Katie, and I share his tastes and have continued this tradition by decorating our home with Indian pots and textiles, Spanish Colonial furniture, and by hanging our walls with the best examples from the Santa Fe Art Colony and Taos Society painters Applegate's watercolor landscapes among them.

Even the former location of the Gerald Peters Gallery at 439 Camino del Monte Sol has Applegate's stamp upon it. While it served us well from the 1970s through the late 1990s, it is still known to some as the "Mary Austin House," and was called by Austin herself Casa Querida, or "Beloved House." Austin was Applegate's good friend, neighbor, and fellow arts advocate who housed artists and intellectuals such as Ansel Adams, Willa Cather, and D.H. Lawrence and helped to found the Indian Arts Fund and Spanish Colonial Arts Society. Austin and Applegate were also active in the local theater scene and friendly with local painting legends such as Andrew Dasburg, Gerald Cassidy, and William Penhallow Henderson, among others. Given the numerous connections I have with Applegate's legacy, it goes without saying that I am thrilled to see this long-overdue tribute to one of Santa Fe's greatest talents come to fruition. My thanks and admiration go out to Daria Labinsky and Stan Hieronymus for their initiation of and devotion to this project, as well as for their thorough research and compelling manuscript. Barbe Awalt and Paul Rhetts of LPD Press are also to be commended for their editorial, financial, and passionate support of this historic project. These people were the true hearts and brains behind this publication. My thanks also go out to all the lenders to this show as well as to the collectors who permitted their works to be photographed by our staff photographer, Joe D'Alessandro. I was flattered to be asked to participate in this project and am proud to sponsor the exhibition, under the direction of Catherine Whitney, which honors the printing of this publication and the seventy-fifth anniversary of the Spanish Colonial Arts Society. It has been a pleasure to work with everyone involved and to "get to know" Frank Applegate a little bit better as a result of this project. -- Gerald P. Peters

The extraordinarily talented Frank Applegate died prematurely at his Santa Fe home in 1931. Well-known in his day as an artist, collector, craft revivalist, and author, he is now largely forgotten. This splendid, readable biography should help make his name familiar once more. I give it an enthusiastic recommendation. -- Dr. Marc Simmons, historian

The contemporary Hispanic artists of New Mexico - especially the modern-day santeros - owe a great deal to the visionary artist Frank Applegate. He helped to set the stage for the modern world to appreciate, collect, and love the religious art of my people. -- Dr. Charles M. Carrillo, anthropologist/santero

Carefully researched and elegantly written, this volume provides a well-rounded portrait of Frank Applegate, an artist who made significant contributions to the culture of Santa Fe in the 1920s. In telling Applegate's story, the authors provide a fascinating view of life in Santa Fe during that time. This book is lavishly illustrated with old photographs and pictures of Applegate's art work. -- Dr. Robert R. White, historian

Background

One of the apparent contradictions of the century through which we have just passed is that the movement in the arts called modernism was actually quite conservative: It sought to preserve what is of the essence and to dispense with the superficial. A powerful tendency in modernism was the search for essential forms in nature and in traditional and so-called primitive arts. Frank Applegate, as made amply clear in the present book, was thoroughly a modernist in his painting and sculptural work and simultaneously he was attracted to the Indian and Hispanic cultures of New Mexico. Like many of his contemporaries who were drawn to New Mexico, he saw that these indigenous cultures still retained much of their traditional character. Artists like Applegate saw the values and forms of these cultures as a restorative against the alienation of modern American life and as an inspiration for their own work.

Within two years of his arrival in New Mexico in 1921 Applegate became an eloquent advocate for both Pueblo Indian and Hispanic culture, and he began a systematic program for preservation and revival of traditional Hispanic crafts. His virtually instant advocacy for these arts suggests that he was well prepared for what he found in New Mexico. In this essay I want briefly to consider some of the intellectual influences which led Applegate to play such a prominent role in the birth of the Hispanic crafts revival in New Mexico.

Frank Applegate and his friend and collaborator Mary Austin were immersed in the philosophical movement which has latterly been labeled "anti-modern." This movement found its roots in the reaction against industrialism which began at the end of the 1700s with the Romantics such as Blake and Wordsworth and was elaborated by John Ruskin and by William Morris and others attached to the Arts and Crafts movement of the late 1800s. While much of the Arts and Crafts movement was bent on reviving European crafts, there also began a gradual revaluation of indigenous and folk arts in other parts of the world, which in the throes of industrialism and Victorian civilizationism had previously been denigrated and ignored.

One of the leading proponents of the new appreciation and revival of traditional arts was the thinker, artist, and art historian Ananda Coomaraswamy. Starting in 1905 in Ceylon and India with an eloquent series of articles, books, and exhibitions, he portrayed the deadening effects of colonialism on local communities and the need to nurture and revitalize handcraft traditions. Other Indian nationalists advocated local craft production as a bulwark against economic and political control of Indian life by the British, but at the heart of Coomaraswamy's thought was the need for spiritual and cultural preservation and revival. Only by preserving core values which recognized the beauty and meaning in traditional Indian forms could a true nationalist movement be based, a movement that could free itself not only from Western economic and political domination but also from cultural domination. Following the lead of Ruskin and Morris, Coomaraswamy decried the mediocrity and uniformity of machine-made products as well as the sapping effects of factory work upon laborers and the meaninglessness of an industrial culture no longer based upon spiritual traditions. Coomaraswamy's ideas helped set the stage for the full-scale incorporation of handcrafts into the Indian nationalist movement led by Mohandas Gandhi.

The close parallels between the ideas espoused by Coomaraswamy in the early 1900s and those of Frank Applegate and Mary Austin in the 1920s suggest intriguing possibilities of intellectual influences. It is likely that John and Mary Mowbray-Clarke in New York were an important conduit for some of these revivalist and anti-industrialist ideas. As well documented in the present book, the Mowbray-Clarkes were close friends of Frank and Alta Applegate. Applegate first met the sculptor John Mowbray-Clarke in 1914 and appeared with him in several group exhibitions. He was a frequent visitor to Mary Mowbray-Clarke's New York bookstore and gallery, The Sunwise Turn, and he and Alta often visited the Mowbray-Clarkes at their Rockland County home.

The Mowbray-Clarkes were also among Ananda Coomaraswamy's first and closest friends after he moved to the United States in 1917. Coomaraswamy's frequent visits to New York centered around the lively atmosphere at The Sunwise Turn, and he also often stayed with the Mowbray-Clarkes at their country home. In 1918 Mary Mowbray-Clarke published under The Sunwise Turn imprint Coomaraswamy's important book, The Dance of Shiva, which included much discussion of his ideas about cultural preservation and revival. Alta Applegate owned this book; her copy (signed by her on the front flyleaf) was until recently in the possession of the present writer. In 1919 The Sunwise Turn published a catalogue of John Mowbray-Clarke's sculpture, with text by Coomaraswamy, and in 1920 they published Coomaraswamy's Twenty-eight Drawings, an exhibition of which came to Santa Fe in the same year. We don't know if Applegate and Coomaraswamy ever met, but all of these Sunwise Turn publications came out while the Applegates were still living in the East, prior to their move to New Mexico and while they were in frequent contact with the Mowbray-Clarkes.

Meanwhile Coomaraswamy himself had visited New Mexico in the summer of 1917. An article in El Palacio in 1920 concerning the show of Coomaraswamy's drawings at the Fine Arts Museum in Santa Fe discusses his visit three years earlier when he had been the guest of William Penhallow and Alice Corbin Henderson, later neighbors and close friends of the Applegates: "It is worth noting, incidentally, that Mr. Coomaraswamy ... was one of the first to appreciate the work of the Pueblo Indian artists, which has recently excited so much interest in New York. He purchased at the time, from Mrs. Abbott at the Rito, two of the water colors by Alfonso Roybal [San Ildefonso Pueblo artist Awa-Tsireh] whose work is perhaps the finest and most progressive of the Indian artists, and who was, in fact, the initiator of the 'movement.'" Writing in 1945 Alice Corbin Henderson recalled her and Coomaraswamy's visit in 1917 to Bandelier National Monument, where through Mrs. A.J. Abbott they discovered Awa-Tsireh's watercolors, which Coomaraswamy immediately purchased.

Coomaraswamy, then a well-known art historian just hired by the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, clearly helped to spark interest in Awa-Tsireh and other Pueblo artists, just as he had years earlier supported the work of young painters in India working in traditional styles. He was also one of the first to recognize the significance of Navajo Indian sandpainting and later wrote: "The Amerindian sand-paintings, considered intellectually, are superior in kind to any painting that has been done in Europe or white America within the last several centuries."

Prior to moving to the United States Coomaraswamy was a leader in the English Arts and Crafts movement, and he had a close relationship with two prominent anti-industrialists, A.R. Orage and Arthur J. Penty. Orage and Penty were proponents of "guild socialism," a movement to restore the means of production to workers through revival of handcraft production along the lines of medieval guilds. Coomaraswamy contributed several articles to Orage's weekly, The New Age, and in 1914 he collaborated with Penty in editing the book Essays in Post-Industrialism. Penty later credited Coomaraswamy with coining the term "post-industrialism," and he was strongly influenced by Coomaraswamy's much earlier discussions of handcraft production in India under the guild system, such as his 1908 publication, The Indian Craftsman. As the authors discuss in the present work, Orage had a later influence on Frank Applegate, when in the 1920s he established a Gurdjieffian group in Santa Fe which met weekly at the home of the Applegates and also at their neighbors, the Hendersons. It is likely that Applegate had long been familiar with the work of Orage and Penty through The New Age, and through Penty's several books on the philosophy of guild socialism. One of these books, A Guildsman's Interpretation of History, was published in America by Mary Mowbray-Clarke under The Sunwise Turn imprint in 1919.

Arriving in Santa Fe in 1921, Frank Applegate quickly immersed himself in both Indian and Hispanic cultures and began building an important collection of "Spanish colonial" arts and crafts, focusing particularly on religious images. Within a short period of time he and Mary Austin conceived the idea of the Society for the Revival of Spanish Colonial Arts (later the Spanish Colonial Arts Society) to preserve historical pieces and promote revival efforts among rural Hispanics in New Mexico. Applegate's ideas at this time clearly reflect those outlined earlier by Coomaraswamy and Penty. Writing in the 1920s (an essay which he sent to the Mowbray-Clarkes), he noted that Hispanic crafts had reached near extinction due to "the American traders and exploiters who by their superior aggressiveness forced their machine-made civilization on them. Now cheap colored lithographs are taking place of the old gesso on wood paintings. Cheap cotton goods are replacing their wonderful weavings." The efforts of the arts society and its leaders, like those of Coomaraswamy, went beyond the crafts revival to recognize other important aspects of traditional Hispanic rural culture, such as music, poetry, and religion.

One of the most essential of Coomaraswamy's ideas in dealing with the situation in India was the notion of "svadharma," which may be rendered in English as "true vocation": every being can and should do work that is in conformity with his or her own nature. This ancient concept is of great significance, for it allows individuals to bring to fruition what is deepest in themselves and in their cultural heritage. In the modern era svadharma inevitably comes in conflict with industrialism, which in the name of economic efficiency ignores the innate skills as well as the cultural traditions of workers and treats them as anonymous cogs in the industrial enterprise, enslaving them in deadening factory work. Through revival of crafts, individuals could continue to be artists and artisans in their own traditions instead of being forced into factory work. In Coomaraswamy's terms, a crafts revival could realize not only svadharma but also "svaraj," that is "self-rule" or "own country," the regaining of economic and political autonomy by the local community.

In Hispanic New Mexico a colonialist situation prevailed that was very similar to India. Since the arrival of the Anglo-Americans in the mid-1800s, local communities had lost their autonomy; their former self-sustenance had been replaced by reliance upon products made and sold by the colonizers. Like Coomaraswamy in India, the Hispanic revival movement also envisioned a larger revitalization of village life, reversing the process of depopulation and loss of economic viability. These concepts were at the root of the ideas of Frank Applegate and Mary Austin, and to large degree they were realized over the succeeding decades after the deaths of these two pioneers: first in the blossoming of the Hispanic crafts revival in the 1930s and later in the present crafts revival which began in the 1970s. Thanks in part to the efforts of Applegate and Austin many Hispanic artisans in New Mexico today live comfortably from their art, and in so doing they fulfill Coomaraswamy's concept of svadharma: "Being a vocation, his art is most intimately his own and pertains to his own nature, and the pleasure that he takes in it perfects the operation. There is nothing he would rather work at than his making; to him the leisure state would be an abomination of boredom." -- William Wroth

Reviews

To truly be able to appreciate works of great art and the circumstances within which they were created require a knowledge and understanding of the life and times of the artists that create them. In "Frank Applegate of Santa Fe: Artist & Preservationist" students of this southwestern artist will be delighted with this elegantly written, carefully researched, informed and informative study. Co-authors Daria Labinsky and Stan Hieronymus bring a beautifully designed, profusely illustrated, and superbly presented compendium showcasing the life and works of Frank Applegate and his influence. Stan Hieronymus focuses upon Applegate's personal family history to life writing with an especial authority as his own father was Frank Applegate's nephew. Accessible written, and displayed with photos of family and Applegate's works of art (some of which have become well known nationally), "Frank Applegate of Santa Fe Artist & Preservationist" has been awarded the Southwest Book Award and is a valued contribution for personal, academic, and community library 20th Century American Regional Art reference collections and supplemental reading lists. -- MidWest Book Reviews

In this vivid biography of a man whose vision was a key to establishing a serious perspective of the Native and Spanish arts of New Mexico, we also have a visual feast of this talented artist's varied work. Frank Applegate's journey from Illinois farm boy to European art student to New Mexican activist, preservationist and artist lasted a mere fifty years (1881-1931) yet his influences in all areas persist. When he arrived in Santa Fe with his wife and daughter in 1921, he became one of the earliest advocates of "Santa Fe style" and built his homes accordingly, encouraging his friends to do the same. Quickly he became part of the group of artists, writers and others who were responsible for developing The Indian Arts Fund. Pottery was acquired by individuals in the group to give modern Indian artists free access to their own ancient designs and methods. The Applegates also went on to collect Spanish Colonial art around the state. According to his contemporary, writer Mary Austin, "Natives sell to Frank Applegate ... because they recognize in him an appreciation not only of the artistry in their work, but of its human significance." Following his passion, he became a dealer of art and, later, a writer. The most interesting lives are often found at the confluence of personality, time and place. This is certainly true in the case of Frank Applegate who also brought to this part of the world his great gifts of artistry, energy and commitment. An artist well worth remembering. -- Marilyn Abraham, Southwest Book Views, Winter 2002

Reverence for our region's colorful past is also the focus of Frank Applegate of Santa Fe. Applegate, a well-known East Coast artist, moved to Santa Fe in 1921 and became one of the leading lights of the burgeoning young art colony. He became interested in Native American and Hispanic art and culture. With Mary Austin, he founded the Spanish Colonial Arts Society, the force behind Santa Fe's Spanish Art Market, which celebrated its 75th anniversary last month. Applegate was a collector, craft revivalist and author who had an artist's eye for the cultural wealth of his new homeland. After his death in 1931, the Santa Fe New Mexican called his Spanish Colonial art collection "easily the finest in existence, and no man was better informed on the subject. A resolution passed by the Indian Arts Fund organization praised "a life dedicated to beauty, its creation and preservation... In fostering the developments of native arts and crafts, his work was tireless, unselfish, and wise ... He was selflessly willing to lend a hand to the ambitious artist, whether the artist was American, Mexican or Indian ... and his efforts to perpetuate the vanishing treasurers of Spanish Colonial art will live enduringly." -- S. Derrickson Moore, Sun-News, August 9, 2001

When 40-year-old Frank Applegate moved to Santa Fe in 1921 his life exploded into new directions of creativity. He gave up teaching ceramics in New Jersey and Pennsylvania to immerse himself in traditional American Indian and Hispanic arts and culture. At the same time, he took up painting, a new medium for him, applying modernist sensibility to his oil and watercolor depictions of the New Mexico landscape and Native American ceremonies. During the 10 years Applegate lived in Santa Fe before his untimely passing, he also created woodblock prints, ceramic sculptures, and santos; designed and built a number of houses; and was a founder of the Spanish Colonial Arts Society and the Indian Arts Fund. "He also apparently was the main figure responsible for building the collection of the Taylor Museum at Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center," said art dealer Gerald Peters. "Frank had a big impact on New Mexico culture." Applegate also was a bon vivant. He and his wife, Alta, when they weren't out checking northern New Mexico's country churches for cast-off santos, participated in a heady Santa Fe party scene that was not devoid of Prohibition moonshine. Celebrants included artists Andrew Dasburg, Randall Davey and the five artists of Camino del Monte Sol known as the Cinco Pintores; writers Witter Bynner, Mary Austin, and William Penhallow Henderson; as well as visitors such as poets Carl Sandburg and Robert Frost, preservation activist Charles Lummis and San Ildefonso painter Awa Tsireh. Applegate was contemptuous of artists who produced "lovely" paintings of New Mexico for tourists and those who romanticized Indian life. "He was totally committed to the traditions here," said Daria Labinsky, who with Stan Hieronymus wrote Frank Applegate of Santa Fe: Artist and Preservationist (LPD Press, 2001) -- Paul Weideman, The New Mexican, July 20, 2001

This is a long overdue tribute to Applegate, who was a founder and promoter of the arts in early twentieth century Santa Fe. In particular, he was instrumental in the preservation and promotion of Native American and Hispanic arts.

Together with Mary Austin, he founded the Spanish Colonial Arts Society. That Society recently celebrated its 75th anniversary and is still a major force in Hispanic cultural activities.

Applegate was a Renaissance man. Known for his paintings, ceramics, writings, and cravings, he was an Anglo who craved and painted retablos and bultos. He excelled in watercolor and oils. He wrote essays, stories and articles. His book, Indian Stories from the Pueblos, was first published in 1929 and later republished in 1977. A second book, Native Tales of New Mexico, was published in 1932.

The illustrations, including over 100 color plates, are mainly of his work. They show the wide range of his talents. The authors are his great-nephew and his wife who had access to family papers and photographs. There is a bibliography and an index. -- Marcia Muth, Book Chat, December 2001