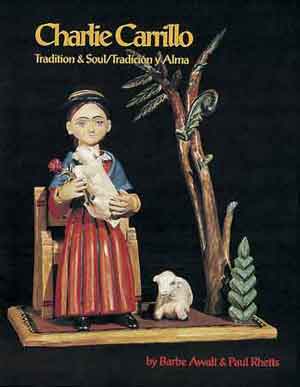

by Barbe Awalt and Paul Rhetts

8-1/2" x 11" 128 pages 293 color plates 7 duotones

SOFTCOVER 0-9641542-0-X $39.95

CHARLIE CARRILLO HAS JUST BEEN HONORED AS A 2006 RECIPIENT OF A NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR THE ARTS NATIONAL HERITAGE AWARD. CHECK OUT THIS BOOK TO SEE A PORTFOLIO OF HIS WORK.

DESCRIPTION

Recognizing the growing interest in Spanish Colonial art, especially from New Mexico, this is the first book on contemporary Hispanic arts and Hispanic artisans. This is the first time a contemporary santero's body of work has been documented.

Charlie Carrillo, an award-winning santero, is considered by many to be one of the masters of contemporary northern New Mexico devotional art. This book documents the major pieces that Charlie Carrillo has produced since 1978 as well as all of his the award-winning pieces, both retablos (flat pictures of saints) and bultos (three-dimensional statues). Carrillo has received top honors in each of the past ten Spanish Markets in Santa Fe including the E. Boyd Memorial Award for originality and expressive design and the Florence Dibell Bartlett Award for innovative design from the International Folk Art Foundation at the 1994 Market. Three of Charlie's Spanish Market award pieces were in the "Crafting Devotions" exhibit at the Gene Autry Western Heritage Museum in Los Angeles. Charlie was also the guest curator of the "Cuando Hablan Los Santos" exhibition at the Maxwell Museum of Anthropology in Albuquerque.

Carrillo has produced some 4,500 pieces in the seventeen years that he has been carving saints. The book displays over 300 of the best and most representative pieces. Examples of Carrillo's work have been taken from many private collections as well as the Heard Museum, Taylor Museum, Tamarind Institute, Museum of International Folk Art, Albuquerque Museum, Millicent Rogers Museum, Gene Autry Western Heritage Museum, Denver Museum and the National Museum of American History/Smithsonian.

AUTHOR INFORMATION

Barbe Awalt and Paul Rhetts are the publishers of Tradición Revista magazine, which focuses on the Hispanic art and culture of the American Southwest, and have published seven books on Hispanic art and culture. They have also curated a exhibit on New Mexican santos - "Our Saints Among Us" - that is travelling to museums and arts center throughout the country through 2002. They are the authors of Charlie Carrillo: Tradition & Soul and Our Saints Among Us, co-editors of Seeds of Struggle - Harvest of Faith, and co-authors of The Regis Santos: Thirty Years of Collecting.

REVIEWS

Interested in getting in on a current art collectors' craze? This time it's the devotional art of New Mexico. A most sought-after artist is Charlie Carrillo. His retablos and santos certainly deserve the acclaim. Carrillo is a remarkable man. He is dedicated to his art, devout and gifted. He is also relatively young and he enjoys his family, friends and community. He is always himself, an engaging man who mainains his particular brand of scholarship, piety and good humor. This book reveals all of this admirably and provides highly satisfactory illustrations of Carrillo's art and of his lifestyle. All New Mexicans can be proud that he is one of us. -- New Mexico Magazine, February 1996

Some time ago there used to be a sign on Highway 159 as soon as you entered New Mexico from Colorado by way of San Luis that said Vaya con Dios. I always thought that a sign invoking the name of God for a safe journey wouldn't last a minute on a highway anyplace in the United States, but, hey, this is New Mexico, a place where you suddenly feel an overwhelming sense of spirituality the moment you cross into it. The profusion of crosses, shrines, and images of saints all along Highway 159 are a sign that you are treading on ground sacred to the people who live in the area. The highway also takes you to the Shrine of Chimayo, a sanctuary sacred to Native Americans and Hispanics alike, where people come on their knees from miles around to profess their faith and allegiance to the miraculous images found in the chapel, surrounded by hundreds of crutches and testimo nials to their healing power. Dozens of chapels and shrines dedicated to different saints, angels, and virgins abound in the countryside where the faithful go to find solace and to commune with their favorite saint.

If we compare this region of the Southwest with other regions in the United States, we find that there is still a place in the U.S. where a unique tradition and belief system, locked in space and time, has managed to survive unchanged in spite of many cultural and religious encroachments from the rest of society. One example of this comparison is the striking difference between Anglo Catholicism and Hispanic Catholicism. When one goes into a Catholic church that is not in the American Southwest, the centerpiece is usually a crucifix with perhaps a statue of the Virgin Mary; the rest of the building is generally stark and simple. A Catholic church anywhere in the Southwest is crowded with saints: pictures, sculptures, crosses, angels, and the ubiquitous representation of the Virgin of Guadalupe. One feels that the whole kingdom of heaven is somehow packed inside that little church. Yet, inside, it is a microcosm of the southwestern world where the daily lives of the people are interrelated with the saints in symbiotic harmony. Take away the saints from the Hispanic and Native American peoples of New Mexico, and we might as well take away their souls.

The Catholic saints are not only a Christian contribution to the religious continuum of the Southwest-they are also the equivalent, to some Native Catholics, of the katsinas, the ancient spirits, the old gods. The indigenous people often ingeniously transferred their gods into the Christian saints, leaving their religious base unchanged. Tonantzin, the mother of the gods, became the Virgin of Guadalupe; Quetzalcoatl became Santiago; Tlaloc, the rain god, became San Isidro, patron saint of farmers. The whole pantheon of old gods reincarnated themselves into San Jose, Saint Jude, Saint Francis, and hundreds of other saints. The Corn Mothers became the virgins: la Soledad, la Guadalupe, del Carmen, la Dolorosa. A virgin for every mood and affliction. The old religion remained almost intact; only the names changed.

A historian once said that without the saints it was doubtful that the Catholic missionaries would ever have converted the Indians in Mexico and the Southwest to Christianity. Understanding the power of the saints, the early padres sprinkled their names over people, mountains, rivers, and cities. Nowhere in the world do we find such a profusion of saints' names as in the Southwest, where great cities like San Francisco, San Antonio, San Diego, and Los Angeles are thriving testimonies to the power of the patron saints after whom they were named. Therefore, the old Kingdom of New Mexico is the "New Kingdom of the Saints," which, according to Larry Frank's book of the same name (New Kingdom of the Saints: Religious Art of New Mexico 1780-1907 [Red Crane Books, 1992]), is the place where the old gods and the new saints still live with the people.

While Frank's book may be the definitive reference work on the world of the saints in New Mexico, Charlie Carrillo: Tradition and Soul, by Barbe Awalt and Paul Rhetts, continues santero research by focusing on the life and work of a specific santero. What makes this book unusual is this focus on a young and modern santero who not only carries on the traditional craft of saint making but also continues to lead the life prescribed by this calling. Charlie Carrillo documents Carrillo's art by merging his life and work as one and the same. The authors trace Carrillo's unique life as an intimate calling to produce this particular art form since he is not part of a traditional santero family but of a family of teachers. This has been a blessing, as Carrillo has imposed on himself the task of passing down the art of saint making by opening workshops for interested people. His calling manifested when he was asked to carry on cultural and archeological research in northern New Mexico on the moradas (chapels) of the Penitente Brotherhood. In these moradas, he came face-to-face with the ancient santos whose mysterious semblance and mystic allure quickly attracted him to learn everything he could about their history and tradition. From then on Carrillo was irrevocably drawn to the saints and the meaning of their involvement with the people. He began to study the craft of the santero with frustrating setbacks as he realized that his own life had to reflect his calling. Charlie married and started a family in which all its members embraced the art and belief in the essence of the santero: "If I didn't truly believe in it," he says, "I couldn't do it. If you don't believe, you are just a painter of images."

In describing the art of saint making, the authors reveal many of Carrillo's techniques and procedures, such as the places he goes to gather the minerals for his pigments, the mixtures required for his many hues, and the types of wood he collects for the sculptures. His artistic trajectory and achievements are documented through his many honors, recognitions, and awards, such as the time he was asked to create a retablo (altar piece) to be given to the king and queen of Spain on the occasion of their visit to New Mexico in 1987. Although not yet 40 years old, Carrillo and his art have become an institution in New Mexico, where he teaches, writes, and gives conferences for several organizations. His santos are included in numerous important collections of religious art in museums all over the world, and his work has been featured in many anthologies and art books. This exceptional book of Carrillo's art was produced by a pair of dedicated authors whose careers and expertise have been grounded in public relations and broadcasting. Their background and knowledge of santero art are masterfully exposed in the presentation of hundreds of beautiful images exemplifying Carrillo's art and work.

Following Frank's important book, Charlie Carrillo is an important contribution to the religious tradition of New Mexico and to santero art. It focuses on a particular saint maker who continues the work and lifestyle of a tradition that not only has endured for hundreds of years but also represents a belief system that continues to thrive among the people of New Mexico.--Bloomsbury Review, June 1997

The New Mexico Book League has named CHARLIE CARRILLO: TRADITION & SOUL as the 24th most favorite New Mexico book. (April 1998)

The first time I saw Charlie Carrillo's work, I was a 15-year-old punk on a school trip to the Denver Art Museum. Then and there, I fell in love with his bright, cartoonish works, painted in a simple style even Giotto would have envied. It's obvious from this new book documenting one of the most well-known santeros in our state that authors Barbe Awalt and Paul Rhetts share the same love for Carrillo's work. Santeros are not folk artists, according to Charlie Carrillo; they are practitioners of a sacred art. But being a santero doesn't necessarily mean one is a holy man; it is about being a historian and educator. Awalt and Rhetts capture these philosophies and the history of this artist and historian, while providing a list of Carrillo exhibitions and an in-depth analysis of religious art. Charlie Carrillo: Tradition & Soul , a gorgeous book filled with photographs of Carrillo's work, is a must-own for collectors. If you haven't seen Carrillo's work, check this out - viewing it is a religious experience in and of itself. -- Weekly Alibi, May 5, 1998